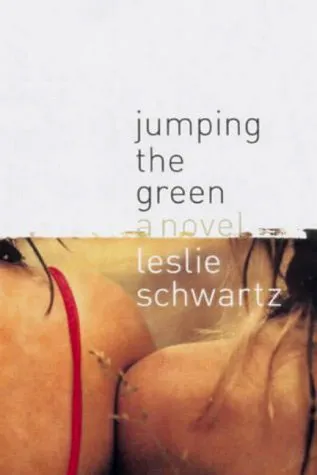

Jumping the green

“…a provocative debut…told with a heat-hazed elegance and subtle control.”

Elle magazine

Winner of the James Jones Literary Society Award for Best First Novel, Published in 3 languages

Louise Goldblum is the new “it” girl on the San Francisco art scene, a sculptor on the cusp of national stardom, when her beloved older sister Esther is shot and killed in a motel room in an old California ghost town. Esther’s sudden, mysterious death sends Louise into a tailspin of mourning and, after a night of hard drinking, into the arms of Zeke Heirholm, a controversial photographer. Volatile and furtive, Zeke draws Louise into a gripping and perilous sexual liaison — and a precarious new terrain of caustic pleasure.

At first, Zeke’s hypnotic charms seem to offer Louise escape from the haunting events of her life — including her tumultuous childhood as the youngest member of the eccentric Goldblum family. But as Louise’s trysts with Zeke become increasingly violent, so, too, does the power of her memories. The further Louise becomes entangled in Zeke’s web, the deeper her mind retreats into the buried layers of her past, revisiting the turbulent and often self-destructive episodes that typified the Goldblum clan. Desperate to escape her chaotic past and tortured present, Louise risks everything — her career as an artist, her relationship with her family — in hopes of carving a path through the debris of her sister’s death and her own shattered life.

Zeke had no hair. Naturally I noticed this first. He had a scar over his mouth, which gave the impression of a harelip, but to my relief later that night when I decided I would fuck him, it was not a harelip. He had three gold hoops in his left ear and a small diamond in his nose. He wore black army boots. But this was not what I was immediately drawn to. On his left arm was a tattoo of an angel. I focused on it like a zoom lens.

“What are you staring at?” he said to me. He had left his table of scary-looking guys — a ragtag ensemble of goatees, tattoos and piercings — and stood at the edge of our table. He was truly menacing though vaguely familiar. I could see the fear on Alice’s face as he fixed his eyes on me. In a complicated medley of shame and eroticism, I thought briefly of Mrs. Kowolski, whose large red nipples were still an inextricable part of my sexual fantasies.

“Nothing,” I said. I looked down at my left hand, which was holding a cigarette, one of the new habits I acquired post-Esther, and saw that it was trembling slightly.

“Bullshit,” he said. He lifted my chin up with surprising tenderness. His hand was strong and white, the veins thick with blood. It was a gesture that didn’t match the threat in his voice. “You’re staring at something. Own up.”

“Your tattoo,” I said. I heard my voice tremble, an egregious mistake, something Esther, I am sure, would never have done. The electricity of her, the way she voyaged fleetingly through my mind, snapped me out of my fear. My subsequent and immediate rage, buoyed by a pack of Kool Milds and several vodkas straight up, gave me courage.

“I’m staring at your fucking tattoo,” I said, testing the waters.

His eyes narrowed and he looked like he might strike me at any moment. Far from being afraid, I was intrigued, a response that fascinated me. I took a sip of my drink, a puff of my cigarette and felt Esther’s soul inhabit mine. I attempted to stare him down. He never relented and I felt my face turning hot, then red. I was grateful that the bar Alice and I chose to get drunk in that night was very, very dark.

“What’sa matter. You have a thing for angels?”

“No,” I said.

He pulled a chair out from under the table, turned it around and sat down so that his legs were on either side of the backrest and his arms draped over the top. He never smiled though I kept expecting him to. Alice kept taking nervous sips of her drink, but it was clear that as far as Zeke was concerned, Alice was not in the room. I glanced at her and could tell instantly that she despised him. He continued to stare at me then slid his finger across my cheek. I felt something stir between my legs. It was then that Alice stood up and rolled her eyes toward the bathroom indicating that I should follow her there.

“‘Scuse me,” I said. I stood up but he grabbed my arm, twisting the skin with his hands. I did not let him see that he had hurt me.

“I’ll meet you at the door in five minutes,” he said as Alice marched away unaware.

I followed Alice to the bathroom without saying anything.

“Jesus H.,” she said. She tapped her long, painted fingernails on the sink quickly, like she was playing an imaginary piano. She bent over and examined her teeth in the mirror, wiping away an invisible smudge of lipstick. “How come we attract all the weirdoes?”

“I kinda liked him.”

She looked at me to gauge the degree of my seriousness. When she saw that I was, in fact, serious, she dissolved into paroxysms of groans and eyeball rolls.

Alice is my best friend, the unfailing rock upon which I have flung myself on more than one occasion. She is everything I have never been.

Number one, she is beautiful. Her hair is blond, she has green eyes and strangely dark eyebrows. Her skin is the color of wheat and her body extremely voluptuous. She has big boobs.

Number two, she is practical and linear in all her thoughts and actions. She never gets hysterical even when situations, as far as I am concerned, demand it. This is best exemplified by her response the time she flew to Arizona and the plane crashed on takeoff, killing three people on board. She left the site of the crash as quickly as possible so she could catch the next plane out. Because of this steely countenance she is the one person I would like to have by my side during a kidnapping or a riot.

Number three, she has a rigid set of personal standard about which she is unrelenting and implacable. These standards are not steeped in morality, but as would be expected, practicality. For instance, she never sleeps with anyone until several months of demonstrated affection and commitment take place, after which time the party in question is expected to test for all sexually transmitted diseases and report back to her with proof of his freedom from disease. This helps explain why she never gets laid.

And last of all, she never lies, even when it would clearly spare another’s feelings, because that way, she says, she doesn’t have to keep track of anything. But, as if to make up for this minor streak of selfishness, she is always loyal and forgiving of others and believes that you achieve the highest state of grace when a friend begins a sentence for the first time with the words, “Don’t tell anyone but–“

” Now she looked at me, having recovered from her seizures of shock and disgust and said, “He’ll hurt you, Louise. Mark my works. I bet if you asked him, he’d admit to torturing helpless little animals. Just look at him, for God’s sake. He looks like the kind of asshole who uses the word cunt to describe a woman. I’m not kidding. This is no laughing matter. You shouldn’t drink if this is gonna be the result.”

“He intrigues me,” I said. I lit a cigarette. “He told me to meet him outside five minutes ago.”

“Don’t go,” she said, touching my arm in a way that made me see she was serious and a little afraid for me. She had been this way for the nearly nine months since my sister died, unsure how to grapple with what she once called my alarming new penchant for one-night stands and vodka for breakfast. She had taken to inspecting me when she thought I couldn’t see her, filling my cupboards up with food when I was out, leaving three or four message on my answering machine when she hadn’t heard from me in a while. She would often say, “You never acted like this before,” referring to the fact that since my sister’s death I had acquired a habit of being late, sleeping through entire days and picking up men with tattoos and earrings. I would hug her for this protectiveness if I were not a Goldblum. Instead, the more Alice tried to steer me from harm, the more I became convinced that I did not need to be protected.

Briefly out eyes caught in the mirror. She saw something in my expression that made her eyes flick away. She clasped her purse shut with a certain finality. On the way out the door she said, “Just don’t let me find you in a goddamned alley with a baseball bat up your vagina.”

I stayed in the bathroom for another minute. I smoked my cigarette and stared at my face. My lips looked drawn and colorless. I was aware of a slight smudge of darkness — not quite circles — beneath my eyes. I looked less like Esther than I would have liked, though my brain was aware that on some level my memory made her more beautiful than she actually was, more exotic and gargantuan in her excess of courage and her cravings for danger. Before I left the bathroom to meet Zeke, I watched myself blow smoke through my nose the way Esther did when she wanted to annoy Maggie and I almost believed I was looking at her. I leaned over and kissed the mirror, leaving behind the imprint of my lips on the glass.

“See ya,” I whispered.

Zeke was standing by the door of the bar when I walked out. He seemed completely unconcerned by the rain. His trench coat flapped around his ankles. His expression did not change when he saw me. He just grabbed my elbow and led me to his car. “Where are we going?”

“You either trust me or you don’t,” he said.

“I don’t.”

“Then it should be more thrilling for you.”

I got in the car with him. Old Toyota, vinyl seats, crystal hanging from the mirror. The fluorescent streetlights made his face look irridescent. The mood exacted by the car, his ghostly face and the rain pelting the windshield reminded me of the sculpture back at my studio, the one sitting there unfinished. Incense and cigarette smells mingled with the scent of rain. “Where are we going?”

He was driving up Divisadero and had turned left on Fell.

“Do you believe in hell?” Zeke asked. He lit a cigarette. He did not use his hands when smoking. He exhaled smoke through his nose, the cigarette gripped between his lips.

“Yes,” I said. I thought of the old homestead, of Esther’s ghost inhabiting it completely. That was a kind of hell. I thought of the ghoulish hell that Catholics had, of all those fires and horned beasts. I thought that hell was more a state of mind than a place. “In a manner of speaking, I think there’s a hell.”

“You were going to make some witty comment,” he said. “I can tell by the way you paused before answering. You were going to repeat something you read in a clever book on popular culture. Something like, ‘Hell is a state of mind.’ I can tell you’re the clever type. Possibly an overachiever.” He stared at me with heroic menace, taking his eyes off the road for an alarmingly long time.

“Are you going to kill me?”

“I don’t usually go that far,” he said. He turned right on Stanyon, then right again and pulled his car onto the sidewalk in front of a massive, dilapidated Victorian with a turret and peeling paint.

“Casa Vincent Price,” I said.

He snickered in a strange way, without smiling. His coat was wet and smelled like Harry the Dog. As we walked up the stairs I thought of all the people I knew who had died. Harry the Dog, not a person exactly, but not a dog either, ran into a moving truck when I was eleven. Mr. Kowolski was electrocuted while pruning the hedges by his swimming pool. Danny Franconi died when his motorcycle went off a cliff in the Santa Cruz mountains. Then there was Esther.

“Of all the people I know who have died, not one of them has done so gracefully,” I said.

He stopped for a minute and turned around. He was two steps above me, looking down at me. He appeared to be amazed, though I was not sure why. Then he walked on. “Are you normally this weird?” he asked.

“This is one of my good nights,” I said.

“Because if you plan on killing me,“ I continued, “Alice knows I’m with you and she says if she finds me in an alley with a baseball bat up my you know what, she’ll cut your…”

“Now that’s interesting,” he said. He rubbed his chin, mockingly introspective. Then abruptly he opened the car door and told me, not unpleasantly, to get the fuck out of the car. I was not afraid. I don’t know why, because my brothers and sisters, Esther especially, have always teased me for being the Goldblum coward. We walked inside the entry, a spooky hallway of white alabaster and gnarled antique chandeliers that gave off a muted yellow glow. There was a library smell of books and dank air about the building that made me feel melancholy. I looked up at the elaborate staircase that spiraled into a domed ceiling. He took my hand and we walked up the stairs. I turned around in time to see one of the tenants open the door and stare at us, then close it again slowly, the hinges howling in the otherwise silent lobby.

We got to his apartment on the top floor and went inside. He did not turn on any lights at first and all I could see was a long hallway and, at the end, a huge bay window and the lights of the city flickering through it. The same smell in his car was in his apartment, a strange, bitter aroma of spices and cigarettes. He went into a room on the left and turned on the light. I looked inside and saw an immaculate kitchen filled, to my surprise, with beautiful old furniture. Several dishes were stacked neatly in the drainer. A large, black-and-white photograph of the backside of a naked woman hung on the wall over the sink. She was lying on a bed, her hands bound behind her. He saw me looking at it.

“Lisa Silburner, 1988,” he said.

There were more. As we moved through the apartment, a studio furnished improbably with elegant antiques, I noticed dozens of photographs, mostly of Lisa Silburner in various states of bondage. In the bathroom there were two photographs, one of a penis, the other a vagina. I wondered if they were Zeke’s and Lisa Silburner’s but could not bring myself to ask, to imagine knowing.

In the main room was a large, neatly made bed. Above it was Lisa Silburner again but this time fully dressed, wearing a hat with a large flower on the front. She was smiling, her lips slightly parted and her prominent nose flaring. Her hair was red and wild. Her eyes, dark and inscrutable. She was oddly beautiful.

“Your girlfriend?” I asked. He took his coat off and stared out the window.

“Not really,” he said.

He hung his coat up in an old armoire. Before closing the doors, I saw a shelf full of camera equipment. Next to the bed was a door with a sign in bold letters: DARK ROOM. YOU FUCKING OPEN THE DOOR, I FUCKING KILL YOU.

There was a large poster on the main wall. ZEKE HEIRHOLM. JULY 13TH THROUGH JULY 19TH. Below the words was a black-and-white photograph of two hookers standing beneath a Guess jeans billboard depicting a hooker wearing Guess jeans. The Guess model did not appear to be as quietly desperate as the real hookers. Under the picture was the address of a gallery on Gough Street./span>

“Are you a photographer?” I asked.

He glared at me. Then he lit a cigarette and sat down on the edge of the bed. Stupid question.

“I like tying women up,” he said. “It’s my thing. I’m telling you that now before you take your clothes off because I’m a decent guy. But once you take your clothes off you’ve agreed to go the distance. I might hurt you. I haven’t killed anyone. Not yet. The safe word is cease. You say cease, I stop. Stop does not mean stop. No does not mean no. Cease means no. Cease means stop. Do you understand? We can start slow. But we don’t stay slow. Not over the long haul.”

It sounded like a job interview. But I hardly knew what he was talking about. I lit a cigarette. My hands were trembling.

“You got anything to drink around here?”

He produced a bottle of something and two shot glasses. He handed me one of the shot glasses. There was an image of a cable car on its surface. I drank the contents. Ouzo. I thought about calling a cab. I looked at the picture of Lisa Silburner, 1988, fully clothed, of the contempt in her beautiful face.

I remembered how my brother Eddie had told me he was “eradicating” just moments before he hacked his finger off. I thought about how some things have their own momentum, their own way of launching forward, pushing aside the cluttered flotsam of all expectation. Progress is not linear, I thought.

“No black eyes,” I said, unbuttoning my jeans. “I got an appointment tomorrow.”

reviews

Amazon Reviews

interview

Beatrice.com

Leslie Schwartz

“Everybody calls this a dark book, but I think it’s a book about hope.”

Leslie Schwartz’s debut novel, Jumping the Green, traces the downward spiral of San Francisco artist Louise Goldblum into alcoholism and sadomasochistic sexuality–assisted in her degradations by a photographer named Zeke who picks her out of the crowd at a bar one night–as she struggles to come to terms with the death of her older sister, Esther. Even before the official publication date, Schwartz (who had spent several years as a freelance journalist for women’s magazines while working on short stories in her spare moments) had received the James Jones Literary Society award for best first novel. We met at the Standard in West Hollywood and talked over iced teas.

RH: As you were writing your short stories, did you know that you wanted to eventually write a novel?

LS: No. The short story just got longer, I just kept writing. I was working as a secretary at the time, a demeaning job in a lot of ways. I took my boss’ laundry to the laundromat, I took care of his children when he was going through a divorce–but in exchange for that, I got to write at work. So I started writing this short story, and it just kept getting longer and longer. I didn’t expect it was going to be a novel at all–it just turned into that.

RH: What part of the story came first for you? Was it the first scene in the published novel, with the young Louise?

LS: Yes. It began with the girl on the raft, discovering her sexuality and living in her dysfunctional family. Suddenly I got a structure going between what was happening to Louise as a child and her relationship with Zeke as an adult. But it wasn’t thought out. I didn’t draw a picture, it just happened.

RH: As you got deeper into the story, did you at any point step back, surprised at where it was going?

LS: No. The only surprising thing for me has been the publishing process, dealing with agents and editors, how supportive they’ve been. As far as the process of the writing, and the story, it’s very germane for me to just write. It was fine. It felt very natural.

RH: So there was no trepidation as the story headed into the psychosexual territory?

LS: What do you think?

RH: Well, I’m working on my first novel. When a relationship in it went in a direction I wasn’t expecting, I wrote that first scene, then stepped back and said, “Am I prepared to write about this?” In particular, I’ve seen a lot of bad writing about sexuality and eroticism, so I felt that if I was going to write about it, I knew I had to be ready to do it right, that the writing would be as good as it was in other scenes.

LS: For me, the sexual stuff is always going to be easier to write about. I stepped back on the stuff about her family; that was much more painful for me to write. That’s probably not what you want to hear, but the sexuality was actually fairly simple to me. When I look back at the book now, it’s almost embarrassing. I feel as if the sex is almost superficial and immature. The best parts of the book, really, are when she’s dealing with her family, because they were harder for me to deal with.

The book was never meant to be erotic. People keep classifying it as erotic, and that pisses me off. I don’t think it’s erotic at all. I think that Louise got into a bad relationship with somebody who abused her, who really hurt her–but she made the choice to get into that relationship. The sexuality in the book is about self-annihilation. Some people deal with their pain through drinking, some through sexuality, and some people by killing themselves. I think that…it was easy for me to write about a guy doing this to a woman, because women make choices like that when things have gone wrong in their lives. It’s so much easier than saying, “Things have gone wrong in my life.” And it’s also phonier in a lot of ways.

A lot of people, especially straight guys, hate this book. They don’t understand why a woman would make that choice, and when she does, it pisses them off. My thinking is that she made the choice to go into this relationship, and he willingly participated, too. They played a game with each other, and that’s hard for people to accept. Their relationship has nothing to do with love, but they were drawn to each other. I firmly believe people can be drawn to each other for the wrong reasons. Louise hates the guy, but she’s sexually drawn to him. There’s no romantic connection at all.

You know what I really want to say? Louise made the choice. Women make the choice, so do men. It shouldn’t be so taboo, so startling to people, to hear about that. I chose to express Louise’s grief through a very detrimental and degrading sexual experience, but I could have done it another way. Heinrich Boll has the protagonist of The Clown put on a clown suit. It’s not about the sex. It’s about the choice to degrade yourself, the choice of not being happy. It’s about not being able to recover from what hurts you the most in a positive way.

RH: Do you see it as ironic that you’ve fulfilled your artistic vision by writing about somebody who negates herself?

LS: I love this character, and maybe that’s why it’s so painful for me to read the book now. I think Louise couldn’t find the grace to love herself through the grief of her family life, so she did the easy thing. She drank and fucked some guy who had no respect for her.

Everybody calls this a dark book, but I think it’s a book about hope. Anybody that can recover from those experiences and survive, as Louise does–that’s a hopeful thing. I don’t believe this is a sad book. What she went through is sad- -but that’s not who she is. When you talk about choice…she made a choice at the end, to survive. She didn’t want to die. She didn’t want to be the girl destroyed by her sister’s death, by her sexual choices. I give Louise a lot of credit. She’s a very courageous person.

RH: She finds the courage to accept the love of her best friend, Alice.

LS: I can’t read the chapter near the end, with the two of them in the restaurant, anymore without crying. It’s just so amazing to me that somebody would love someone as much as Alice loves Louise, that she’s willing to forgive so much. When I read that scene, I think Louise is so lucky that Alice forgives her…

RH: And this is nearly three years after you wrote it. How did it affect you then?

LS: It didn’t. It wasn’t until later that it hit me. And there’s some scenes that I can’t read at all now, I find them so sad.

RH: Who are some of your favorite fiction writers?

LS: I like Francine Prose a lot. I think she’s great. I liked Susanna Moore’s In the Cut. I love Mary Gaitskill…she’s an amazing writer.Her stories are scary. I want to meet her; I’m just blown away by her talent, her willingness to take risks. I like writers who push the limits a bit. I tend to like writers that other people haven’t heard about.

There’s a short story by Lorrie Moore about a baby that almost died; people have asked her if it’s autobiographical or not. So at one event, she was asked to read that story, and she got three minutes into it, then left the podium crying. I didn’t see this, I read about it in the New York Times. And the author of that article raised a great point–what does it matter if this happened or not? It’s a powerful story, and a story is a story. Does the fact that it happened or not make it any less a story if the story is well told? No, it doesn’t. Is the story good? Is the writing good enough to keep you interested? That’s what I think is the relevant question.